Greek civilization was tagged classical because many of their contributions are still widely patronized by many.

Ancient Greek arts have contributed much to our civilization particularly in the areas of sculpture and architecture. Their art have influenced the world over up to the present although much of their works have been destroyed and only a few survived. Here are the ten most famous surviving Greek sculptures.

The statue of Aphrodite de Milos is regarded as the most beautiful model of a woman’s body. It is at present on display at the Louvre Museum in Paris. It is an ancient Greek statue and one of the most famous works of ancient Greek sculpture. It was created between 130 and 100 BC, it is believed to depict Aphrodite (called Venus by the Romans), the Greek goddess of love and beauty. It is a marble sculpture, slightly larger than life size at 203 cm (6.7 ft) high. Its arms and original plinth have been lost. This contributed to the mystery of the sculpture. It is believed to be the work of Alexander of Antioch

Laocoon and His SonsThis sculpture is also called the Nike of Samothrace. It is a third century B.C. marble sculpture of the Greek goddess Nike (Victory). Since 1884, it has been prominently displayed at the Louvre and is one of the most celebrated sculptures in the world. The work is notable for its naturalistic pose and for the rendering of the figure’s draped garments, depicted as if rippling in a strong sea breeze, which is considered especially compelling.

The statue of Laocoon and His sons is also called the Laocoon Group. It is another monumental marble sculpture housed in the Vatican Museums in Rome. The statue is attributed by the Roman author Pliny the Elder to three sculptors from the island of Rhodes: Agesander, Athenodoros and Polydoros. It shows the Trojan priest Laocoon and his sons Antiphantes and Thymbraeus being strangled by sea serpents.

This Bronze Sculpture is thought to be either Poseidon or Zeus created about. 460 B.C. It is now housed at the National Archeological Museum in Athens. This masterpiece of classical sculpture was found by fishermen in their nets off the coast of Cape Artemisium in 1928. The figure is more than 2 m in height.

This statue is a copy of Polycitus’ Diadumenos located in National Archeological Museum in Athens. The Diadumenos which means diadem-bearer is one of the most famous figural types of Polycitus that present strictly idealized representations of young men in a convincingly naturalistic manner.

The Diadumenos is the winner of an athletic contest at a game, still nude after the contest and lifting his arms to knot the diadem, a ribbon-band that identifies the winner and which in the bronze original of about 420 BCE would have been represented by a ribbon of bronze.

This statue is the so-called Venus Braschi by Praxiteles, a type of the Knidian Aphrodite. It is housed in Munich Glyptothek.

The Marathon Youth is another work of art by Praxiteles. This bronze statue was probably created about 4th century BC. It is located at the National Archeological Museum, Athens.

The Statue of Hermes is created possibly by Pypsippos. It is currently housed at the National Archeological Museum in Athens.

The Charioteer of Delphi in Delphi Archaeological Museum is one of the greatest surviving works of Greek sculpture, dating from about 470 B.C. Part of a larger group of statuary given to the Sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi by Polyzalos, brother of the tyrant ofSyracuse, this bronze in the Early Classical style is one of the few Greek statues to retain its inlaid glass eyes.

The terracotta statue of Zeus and Ganymede, in Olympia Archeological Museum was found in Olympia and believed to be executed around 470 BC. The terracotta is painted.

Greek sculpture was focused on the human body. The above examples were manifestations that Greek sculptors have perfected human anatomy. Every detail of the body curvature was very well presented

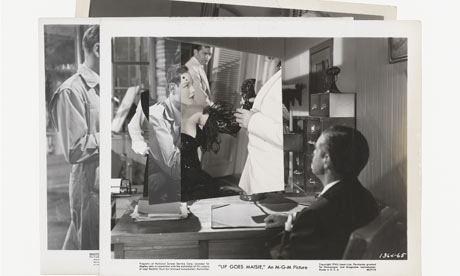

Cut-and-paste ... Untitled: For Angus - Film Still Collage I (2009), by John Stezaker. Image courtesy The Approach, London

With a few deft incisions with his scalpel, John Stezaker reveals what is lurking beyond the glossy surface of postcards and publicity stills. Sometimes one picture is simply positioned over the centre of another, but in a series such as Marriages (2006), men and women are forcibly yoked together with a swift, decisive incision down the middle. In Bridges, Stezaker's ongoing series started in the 1980s, buildings are chopped and reconfigured. Elsewhere the silhouette of a figure is cut out; its ghost-like absence filled in by more landscape or someone else's body. The technique is stunningly straightforward, the effect profound. As strong-jawed men are spliced with B-movie glamour pusses, bodily forms with architectural ones, painstakingly posed promo material becomes unruly, disorientating and freakish.

Stezaker soaked up a variety of influences while studying at London's Slade School of Fine Art in the 1960s. His teachers included Ernst Gombrich, an iconic art historian and Richard Wollheim, the Freudian philosopher. During this time, in France, the Situationist group of artists were arguing that reality had been replaced by the endless flow of images in the capitalist mass media. It was an idea Steazker took to heart, using the most straightforward kind of cut-and-paste to question the meaning of images.

Stezaker doesn't use just any picture: his raw materials are long-forgotten B-movie relics from British cinema, dating back to his childhood in the 1940s and 1950s, or retro picture postcards full of quaint grottos, waterfalls and terracotta roofs. Thanks to Stezaker's weird conjunctions, however, these images seem alienated – cut off from culture, place and time.

His technique has been constant since the 1970s, but success arrived later in life. The past decade has seen extensive solo shows in the US and Europe, and his inclusion in major survey shows such as the 2006 Tate Triennial. Perhaps this recognition has come about because his psychologically charged, modestly-scaled work seems ever more relevant in our technologically supercharged moment.

Why we like him: For Masks (2005), a series in which actors' faces are replaced with postcards of Romantic landscapes. A dark cave, gushing waterfall or train tunnel merges with a perfectly coiffed head. A man's brow slides into a motorway bridge; a craggy rock face stands in for eyes and nose. These are disturbing, dreamlike forms that burrow their way straight to our subconscious.

Poster child: A 1950s billboard advertising Start-Rite shoes introduced the young Stezaker to the hidden meaning of images. Its depiction of children seen from behind as they walk down the long road of life – seemingly towards their death – haunted his childhood.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2010/jan/28/artist-of-week-john-stezaker

Berkeley Brown reflects on the jewellery she creates on the occasion of her first solo exhibition in Halifax, titled “Whisked Away.”

The value of food in our society is fascinating; I am intrigued by the way our relationship to it allows food to transcend its practical role as nourishment, becoming passion, desire, comfort, metaphor, art, chore, social interaction, delight, tradition, or profession. My interest in these issues has led me to make jewellery that comments on them, creating pieces to adorn ourselves in our passions for cooking and food.

Using the aesthetics of cooking utensils, abstracting their function and form, I strive to explore our relationship to food in daily life. I use utensils as a means of evoking our interactions with food because they are connected with tradition and culture. We relate to food through the utensils we use to make food and eat food; for example, the specialized equipment that we rely on to make a cake, from whisk to egg beaters and whether we like to eat the cake with a fork or a spoon. These objects’ beauty of design and function inform my work.

Primarily, my inspiration lies in philosophical and humorous writings on food and cooking which reflect the passion of the writer and carry food into all areas of life. The pleasure and comfort of baking or eating that is reflected in these writings, is the feeling I hope to bring to the wearer of my jewellery.

While exploring food utensils through jewellery, I encourage personal response and interaction: Paper and text are employed to reference the passion surrounding food as expressed in food writing and moving parts allow the wearer to interact with the pieces. My jewellery is informed by the mechanics of utensils, though I leave the practicalities of the original utensil behind, instead creating functional jewellery. Connections, movement, clean lines and repeating forms are all brought into my work.

My jewellery reflects an investigation of our passion, relationship and the rituals we create around food while integrating my love of technical precision and movement in jewellery.